In the modern corporate environment, the performance improvement plan (PIP) is often introduced as a developmental measure: a structured, documented process designed to help employees address performance gaps and meet clear expectations. At face value, it appears to be a fair and reasonable intervention. Human Resources departments and leadership teams frequently frame the PIP as a supportive measure—a final opportunity for employees to succeed, recover credibility, and realign with the company’s goals. The language used in these conversations is typically collaborative, even empathetic, emphasizing growth and personal development.

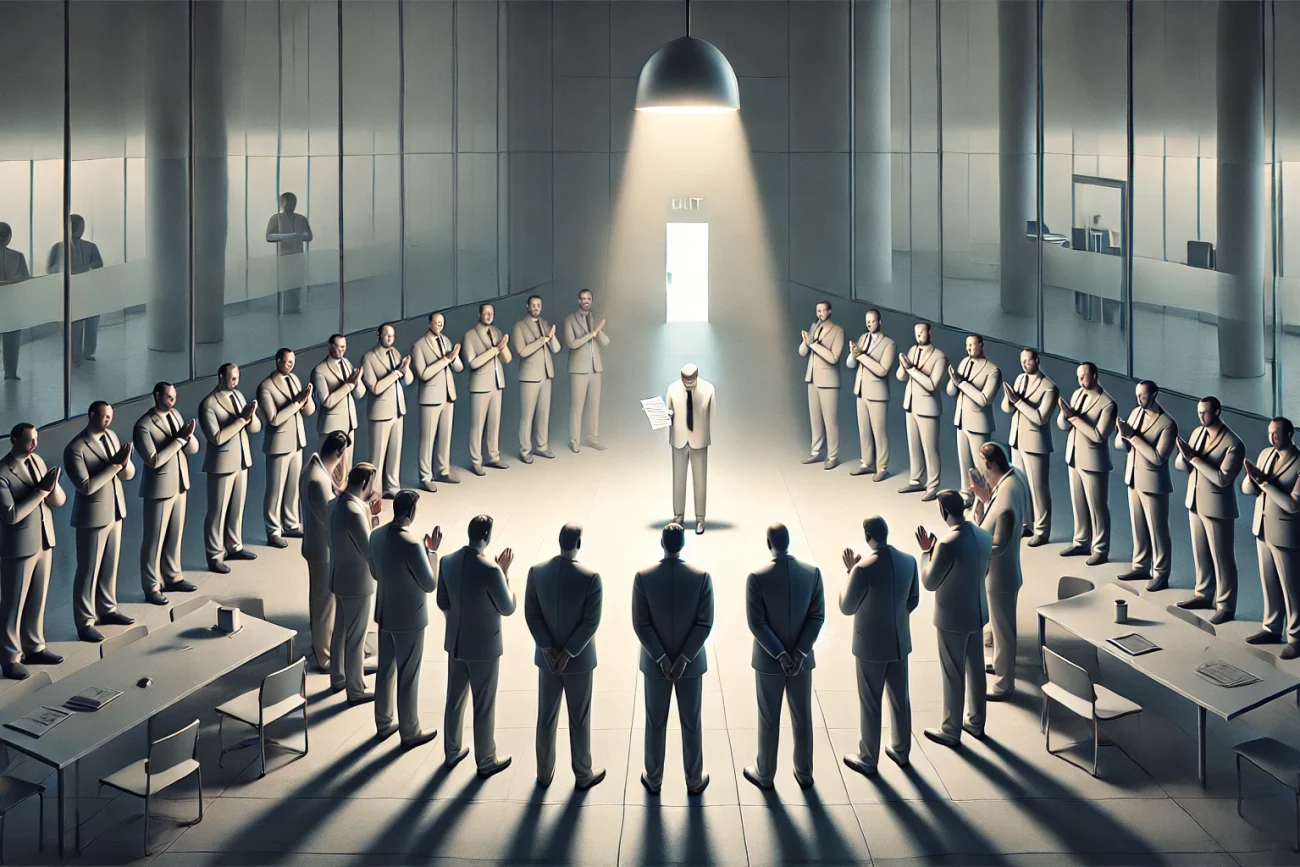

However, the reality experienced by many employees tells a different story. Rather than a genuine performance development plan, the PIP is often perceived as a pretext—less about coaching, more about protecting the organization. It provides legal cover and a written process that can justify future termination, should it come to that. For the employee, the PIP can feel more like a formality than an opportunity, signaling that the decision has already been made. This tension reveals a fundamental contradiction at the heart of many performance improvement plans: they are presented as a lifeline but may in fact be a carefully managed exit strategy. This disconnect warrants closer examination, especially in workplaces claiming to value transparency and trust.

"A performance improvement plan may be framed as support, but for many employees, it’s the beginning of a quiet, structured exit."

The Origins and Evolution of the PIP: Designed for Fairness, Repurposed for Control

The performance improvement plan (PIP), as it exists today, is a relatively modern fixture in corporate life. Emerging in the late 20th century, it was part of a broader wave of HR formalization—an effort to introduce structure, documentation, and accountability into how companies managed employee underperformance. Initially, these plans were positioned as fair and consistent tools. A well-intentioned employee improvement plan would offer clear feedback, measurable goals, and a final opportunity to turn things around before more serious consequences, such as dismissal, were considered. It was a response to an era increasingly concerned with legal exposure and the demand for justifiable, non-arbitrary personnel decisions.

Yet over time, the PIP has shifted away from its developmental origins. While still framed in the language of opportunity, it is often used more for protection than progress. In practice, many organizations treat performance improvement plans less as coaching instruments and more as legal insurance—an administrative shield against claims of unfair dismissal. The process may look supportive on paper, but in many cases it functions more as a carefully managed precursor to termination. The work performance plan that once aimed to uplift has been reshaped into a risk management tool.

This shift has also been quantitative. Data from HR Acuity shows a notable increase in the formal documentation of underperformance, from 33.4 incidents per 1,000 employees in 2020 to 43.6 in 2023. This rise reflects a growing reliance on performance improvement plans as a default mechanism, not a last resort. The implication is clear: the PIP is no longer a rare intervention but a normalized corporate practice. What began as a safeguard for fairness has, in many cases, become a system of control, quietly reshaping the employment landscape.

A False Promise: The Myth of the “Second Chance”

The narrative often attached to a performance improvement plan (PIP) is one of optimism. It is presented as a fair, structured opportunity for the employee to recover, realign with expectations, and demonstrate value. There is talk of support, coaching, and a renewed focus. On paper, the PIP appears to be a thoughtful intervention—a second chance to succeed within the organization. In reality, however, the experience for many employees is far more punitive than productive.

The gap between perception and practice is significant. Employees placed on performance improvement plans frequently report receiving little to no meaningful support. Despite promises of mentorship and feedback, many are left to navigate unrealistic targets under tightly compressed timelines. The goals are often vague or arbitrarily defined, with little connection to day-to-day responsibilities. What is framed as an employee improvement plan too often feels like an exercise in going through the motions, lacking the genuine developmental intent required for success.

The data reinforces this disconnect. According to a survey by Blind, only 41% of employees who undergo a PIP remain in their roles after its conclusion. Other findings indicate that fewer than half of those placed on work performance plans experience any measurable rehabilitation. More importantly, even when employees do meet the outlined objectives, the damage is often lasting. Many report feeling permanently sidelined, excluded from future opportunities, and stigmatized within their teams. The experience can erode confidence, diminish trust, and create lasting doubt about one’s place in the organization.

This raises a critical question: is the performance improvement plan truly designed to foster growth and recovery, or is it simply a procedural step toward a quiet exit? When survival within a PIP still leads to marginalization, it calls the legitimacy of the “second chance” narrative into serious doubt.

Behind the Curtain: Legal and Managerial Motivations

A closer look at the performance improvement plan (PIP) reveals an uncomfortable truth: while it may appear to focus on employee development, its underlying function often serves a very different purpose. In many corporate settings, especially those where legal and reputational risk is high, the PIP acts less as a coaching framework and more as a risk management strategy. Terminating an employee without proper documentation can open the company to claims of wrongful dismissal, discrimination, or unfair treatment. By introducing a performance development plan, employers create a structured paper trail that can be used to demonstrate fairness, regardless of the reality experienced by the employee.

For managers, the PIP also provides a way to avoid direct confrontation. Delivering critical feedback over time, building developmental plans, and supporting long-term growth can be difficult and uncomfortable. Instead, the performance improvement plan offers a formal structure that makes the process appear neutral and objective. It shifts the burden of resolution onto a document, rather than requiring active leadership. This makes it easier to justify decisions without engaging in the ongoing effort required to truly support underperforming staff.

There are also more strategic applications. Some organizations use employee improvement plans to quietly manage out senior or high-cost employees. These individuals may be too expensive to retain or perceived as resistant to change, but terminating them outright could raise legal red flags. By using a work performance plan, the company can begin the exit process while protecting itself from potential fallout. Similarly, during headcount reductions, PIPs allow companies to lower numbers without triggering formal layoff processes that could attract external scrutiny.

These patterns suggest that the performance improvement plan often serves institutional interests first, with employee growth a distant secondary concern.

The Human Cost: Stress, Alienation, and Career Damage

While the business rationale for implementing a performance improvement plan (PIP) may appear sound—offering a documented structure to address underperformance—the personal toll it takes on employees is substantial and too often overlooked. The emotional impact begins almost immediately. Being placed on a PIP often feels less like an opportunity to grow and more like a formal warning that trust has already eroded. The process undermines confidence, increases anxiety, and can leave employees feeling isolated and under surveillance.

Many individuals subjected to work performance plans report a sharp decline in psychological safety. Autonomy is reduced, daily tasks are scrutinized, and communication with managers becomes cautious and transactional. Even when the employee improvement plan is technically completed, the stigma tends to remain. Those who “pass” the plan are rarely welcomed back into the fold as equal team members. Instead, they occupy a fragile position—perceived as risks rather than contributors, and often excluded from key projects or advancement opportunities.

This experience leaves lasting effects on both individual careers and workplace culture. Employees who survive a performance development plan frequently describe a sense of career limbo. Promotions stall, performance reviews remain lukewarm, and the social fabric of their working relationships is weakened. The phrase used by some insiders—“walking wounded”—captures the state of those who endure the PIP process but never fully recover within the organization.

The damage extends beyond the individual. When colleagues observe how performance improvement plans are used, they often draw their own conclusions: management appears more focused on risk mitigation than on supporting employees through challenges. This perception fosters a culture of fear and silence, where asking for help may be seen as a liability. Ultimately, the widespread use of PIPs in this way sends a clear message—performance problems are punished, not supported.

The performance improvement plan (PIP) has become a fixture of modern corporate life, but its role as a genuine support system is increasingly in question. While some employees may benefit from clear expectations and focused feedback, these instances are the exception, not the rule. In most cases, the PIP serves less as a tool for development and more as a formal step in managing someone out. It wears the language of opportunity, but in practice, it functions as a signal that the employer has already moved on.

If organizations are sincere about improving employee performance, they need to rethink their approach. Real support comes from early, continuous feedback, accessible coaching, and clear communication—not from a reactive employee improvement plan triggered at the eleventh hour. A culture that promotes growth must integrate performance conversations into its everyday rhythm, not rely on a document to do the heavy lifting when trust has already broken down.

The PIP, as it stands, is less a roadmap and more a red flag. It may offer legal cover, but it rarely offers a path back to professional trust and inclusion. Until workplaces are willing to reimagine what genuine development looks like, the performance improvement plan will remain more punitive than productive.